Two dishwater blond gentlemen were sitting next to me in the Starbuck's "sidewalk cafe" of the infamous black marble and polished steel corporate mausoleum where I sometimes hang out in the morning. They were wearing identical "summer business casual" outfits--blue, open-necked, oxford cloth, button-down shirts with tan trousers.

Even with these they could hardly be comfortable with Columbus' mid-summer weather: in the morning it is a steam bath and in the afternoon it is a slow oven until the severe wind and rainstorms crash through. Undoubtedly both of these men also have a navy blazer, with brass buttons, on a hanger in the work cubby, along with a repp stripe tie, for sudden dress up emergencies during the day.

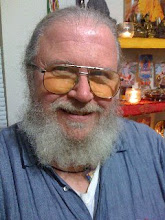

I, of course, was dressed in a blue and silver baseball cap with a Duluth Trading Company logo on the front and my grey ponytail sticking out the back. My straight hemmed, short sleeve sport shirt was equally grey, with a plaid pattern of subs in the fabric resembling those you find on Dad in a grimy black-and-white snapshot, circa 1955, of the trip to Atlantic City and the encounter with Planter's Mr. Peanut on the Boardwalk.

My trousers were of a shy medium brown, with study rivets at all the stress points, and made, of all things, from a variant of the very durable canvas that used to cover firehoses. They complemented my new, dark-blue, single-clip suspenders which look, for all the world, like the straps of a phantom back-pack.

Both the trousers and the suspenders were also from Duluth Trading Company, who deserve a free plug. If you've never encountered them before, you should know that their catalog copy once asserted that these particular suspenders have "a high cool factor, more like wearing a shoulder holster instead of suspenders."

This, of course, is a corporate fib. Nothing you can possibly conceive of in the otherwise worthy town of Duluth, Minnesota has a high cool factor. And the suspenders really do look like your backpack fell off of them twenty minutes ago. They, and the pants, are, however, good hard-wearing clothes and well worth the investment of buying them mail-order and new.

Shopping with DTC is a nostalgic hint of what used to be commonplace in America: corporations prouder of their products than their profits. So, for that matter, is Starbuck's, which is one of the reasons why it gets so much free advertising in these essays.

All in all, you could say that my sartorial style is Early John Deere.

Because of this, I had just been chased away from the impromptu easy-chair lounge with the Isamu Noguchi glass topped tables, recently installed in the hall of the black marbled building, just over from the Starbuck's "sidewalk cafe" with the completely unnecessary sun umbrella. The immigrant security guard--whose navy blazer had a cloth shield on the chest pocket and a metal badge on the lapel--used his keen insight and observation to determine that I was probably not there to do business and shooed me back to the sidewalk cafe, along with my vente coffee of the day in its paper cup.

And there you have a round-up of the moral state of this free country just after the turn of the Millennium.

In any event, my identically dressed and more stylish companions under the green picnic umbrella were clearly there to do business, as I clearly was not, so they didn't appear to give a damn whether I eavesdropped or, equally, whether the echoes of their own vibrant someday-my-company-will-own-the-earth voices in any way disturbed the even tenor of my thoughts.

And if you are wondering why they hadn't the wit to observe the more comfortable lounge not five yards away and sit there, I really can't tell you for sure. But I would note that immigrant security guards are likely to have come from places where the unobservant can have very bad things happen to them. Young, dishwater blond, native-born Americans in blue oxford cloth shirts haven't.

I call them young from the privileged position of twenty years seniority. They were actually just a little over thirty, and so part of that well-known Generation X whose values and attitudes were so opposed to my own, and who would find my nostalgia for product-proud companies either quaint, or, more likely, simply bewildering. So, of course, they were talking of "targeting midlevel markets" and "corporate acquisition teamwork" in the usual dead-metaphor ridden speech we know as American English.

I presume they were in brokering or insurance, since they also spoke of the "post-Spitzer environment", the "profit burden of total transparency", and the "public's need for scapegoats". But it didn't really matter. The gobbledygook is universal, as is its arid contentlessness, and it is stripped equally of human values and human meaning, no matter what particular business is talked about with it.

My Buddhist teachers take great pains to prepare me to die properly. But these fine gentlemen were obviously preparing to live forever with the same blue shirts, tan chinos, and empty cant--emotionally secure in the feeling that no one is ever going to tell them that they have an inoperable cancer, or that they would be far better off in a nursing home while their house is sold to pay the bills.

Amidst all the vapid business blather that they had stuffed themselves with for ten years or more, there was a single, forlorn, human remark. One of them mentioned that he regretted leaving Denver [he was not, of course, born there] to pursue his business affairs in Columbus, "on the district level". It was startling to think that he would even notice.

I, too, left the Rocky Mountain West that I still love, returning to Ohio from Albuquerque to bury both my parents. Luckily, only one of them saw the inside of a nursing home, for about a month, and that mainly for hospice care. I remain in Ohio because I am impoverished and my companion, who is totally disabled, probably couldn't stand the move.

But I can practice Buddhism anywhere, just at they can do business anywhere, even if "not at the district level". And since they are going to live forever, the lack of enthusiasm for Columbus matters very little. After all, they can always go wherever they want to live sooner or later.

Sooner or later.

Friday, August 3, 2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)